Downwell Packs a Lot into Few Pixels

Downwell is a fast-paced minimalistic "rogue-liteish" game, published in 2015 by Devolver Digital. It's available on many devices large and small. I played the PS4 version. The game is unsurprisingly about a guy falling down a well. During his neverending dive the hero utilizes his gunboots to dispose of various beasts such as spiked snails and floating eyeballs, and collects a truckload of gems on the side.

The game excels in playability and visuals. I want to dig deeper into the visuals and compare it to the retro visual trend that's been going on in modern indie games for quite some years now.

Downwell is drawn mostly in only three colors. Graphical fidelity is exaggeratedly low; pixels are scaled up by a factor of 3 or 4. The result is virtually a 2-bit 550×310 video mode of which the real action takes only the middle vertical third. Looking at it reminds me of the home computers of the early 1980s such as the ZX Spectrum, and of later game consoles such as Nintendo Game Boy. These gaming platforms had very limited graphics capabilities compared to nowadays.

Retro visual style, or making modern games look like they were made in the 1980s, is a long-lasting trend in indie games. Whereas in the old times this style of visuals was dictated by the physical limitations of the devices, nowadays the same style works just as well to cope with limited production resources. The game developers may not be able to spend much money and effort on visual content.

A small indie game development team may also lack the graphics skills to produce graphics that took use of modern graphics capabilities. Presenting a game as following the old visual limitations is a clear choice of style and can easily make the game more appealing than if striving after the modern visual look and falling short.

I have only very limited experience in creating computer graphics, but my firm understanding is that 2D graphics is much more straightforward to create in terms of the complexity of the necessary tools. This is, however, not to say that 2D graphics is necessarily easier to create. I believe that regardless of the technical style of graphics, the quality of the end result is always mostly up to the artistic skill of the individuals who put their effort into the creative process.

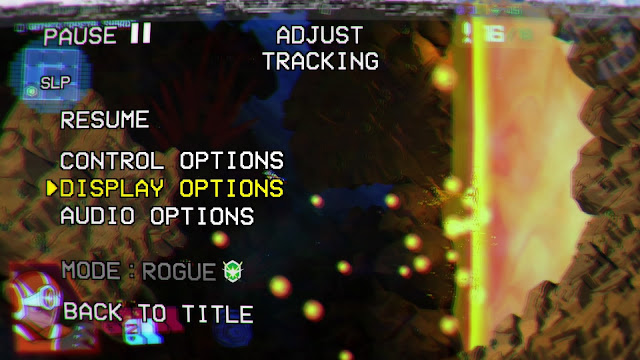

It seems that retro style "filters" are applied to some games just for the sake of appearing more retro. Sometimes these filters are presented to the player as optional. Switching them on from the game menu can be considered as a fun gimmick for nostalgia's sake or for momentarily shaking up the game for a bit of a different kind of play experience.

Other times the filters are compulsory. Compulsory use of retro filters in modern games can be conflicting. In the old times the "retro style" was an unavoidable fact forced by contemporary technology such as limited graphics chips. Some could only produce 16 fixed colors total in a resolution where pixels were taller than they were wide. Monitors often projected their image on a curved glass surface that made straight lines bend. The picture signal was transmitted through an analog cable that added visible noise. You could even hear a buzzing noise that got the louder the brighter the screen was. These effects were not option but unavoidable limitations that had to be tolerated and worked around. Modern games that use retro filters that bring some of these adverse effects back are essentially putting extra effort in reducing the quality of the experience. I do recognize the appeal of nostalgia from being able to experience the technical limitations of times past. However, forcing that on a game is missing the point. These limitations are not what made some of the old games great. They merely accompanied the old gems. Old classics were great despite their limitations.

One example of applying retro filters with good taste is Galak-Z: The Dimensional. It's a rogue-lite 2D space shooter that is made to look like a 1980s cartoon series. One important artistic detail to carry that feeling is how the pause screen of the game looks like you've pressed pause on your videocassette recorder that's hooked to a cathode ray tube TV. There's warping of straight lines, garble at the top of the screen, color distortion, and even a typical VCR system font.

The hero is drawn in two colors into an area of about 10×10 virtual pixels (about 35×35 actual pixels on a modern FullHD display). He's vividly animated, and the animation is not only eye candy but carries a meaning. The choice of game mode is called a "style" in Downwell. You start with Usual Style which has the hero running in a vivid but... usual way. Then there's Arm Spin Style which is like Usual Style but the hero is flailing his hands around like they were dangerous weapons. Not only does it look amusing but it conveys point of the game mode; you only find gun modules and no gem stashes. Then there's Boulder Style which makes the hero move by somersaulting instead of running. As you'd expect, boulders are resilient and immutable, and consequently the hero has more health and less upgrade options.

From a technical point of view, the game uses three colors to draw enemies: the background color, the foreground color, and the highlight color. The highlight color is used in two ways. First, when used in small amounts it's both a stylistic highlight and a signal that this is an enemy. All safe objects such as plain walls and breakable props are drawn without the highlight color. The second way that enemies use the highlight color is that when an enemy is not safe to jump on then it's drawn with more highlight color than foreground color. The ample use of highlight color shouts of danger like a poisonous mushroom in a forest. The same logic is used later for traps as well. A wall that will hurt you is drawn mainly in the highlight color.

From a technical point of view, the game uses three colors to draw enemies: the background color, the foreground color, and the highlight color. The highlight color is used in two ways. First, when used in small amounts it's both a stylistic highlight and a signal that this is an enemy. All safe objects such as plain walls and breakable props are drawn without the highlight color. The second way that enemies use the highlight color is that when an enemy is not safe to jump on then it's drawn with more highlight color than foreground color. The ample use of highlight color shouts of danger like a poisonous mushroom in a forest. The same logic is used later for traps as well. A wall that will hurt you is drawn mainly in the highlight color.

Another notable thing about the colors is how much the choice of the three colors can express. As you play Downwell you unlock different palettes. It's purely a visual thing and doesn't affect gameplay. The GBOY palette looks unmistakably like the monochromatic screen of Game Boy. The MATCHA palette, on the other hand, looks very much like powdered Japanese green tea. The GRANDMA palette looks to me like a blueberry pie and justifies the name adequately. :-) These mental associations are brought up by the choice of mere three colors.

Another notable thing about the colors is how much the choice of the three colors can express. As you play Downwell you unlock different palettes. It's purely a visual thing and doesn't affect gameplay. The GBOY palette looks unmistakably like the monochromatic screen of Game Boy. The MATCHA palette, on the other hand, looks very much like powdered Japanese green tea. The GRANDMA palette looks to me like a blueberry pie and justifies the name adequately. :-) These mental associations are brought up by the choice of mere three colors.

Visual bandwidth is the amount of information that can be encoded into the visual stream that a game presents to the player. To rule out silly applications of this term I'd only consider encodings that are legible by a normal human being. So, visual bandwidth is not the bit depth times number of pixels times screen refresh rate. Rather, it's a measure of the style of how a game presents itself considering the guidelines of its chosen visual style. If a game decidedly uses only dark and drab colors then its visual bandwidth is narrow because information cannot be encoded into distinct colors. If a game likes to present information in full sentences of written text then it has a wide visual bandwidth at least when it comes to conveying narrative. It's also possible that a game utilises some clever graphical presentation that can deliver narrative with an even wider visual bandwidth than text-based presentation could. And even though text may have a wide bandwidth for presenting narrative it probably has a very narrow bandwidth for presenting spatial information in a fast-paced shooter.

Gameplay space is the collection of possible game states. A game with many independent objects will have an enormous gameplay space. Only state that essentially affects gameplay should be included in gameplay space. Things that are just for show are not relevant for this concept.

|

| Watch it, you're about to fall down the well! |

The game excels in playability and visuals. I want to dig deeper into the visuals and compare it to the retro visual trend that's been going on in modern indie games for quite some years now.

Downwell is drawn mostly in only three colors. Graphical fidelity is exaggeratedly low; pixels are scaled up by a factor of 3 or 4. The result is virtually a 2-bit 550×310 video mode of which the real action takes only the middle vertical third. Looking at it reminds me of the home computers of the early 1980s such as the ZX Spectrum, and of later game consoles such as Nintendo Game Boy. These gaming platforms had very limited graphics capabilities compared to nowadays.

|

Fairlight: A Prelude (1985, ZX Spectrum), and Tetris (1989, Game Boy).

Screenshots taken from Wikipedia. |

Retro Visuals

Because Downwell's graphical fidelity resembles that of old games, I first thought that Downwell is going for the retro visual style. However, more recently I understood that this was a hasty judgment. Downwell is not retro but minimalistic. The fact that minimalism and retro look alike is coincidental. I suspect that this small difference in what I imagine was Downwell's visual design guide makes the game that much fresher and more enjoyable. But now I'm jumping ahead of myself. Let me talk about the retro visual style in other games first.Retro visual style, or making modern games look like they were made in the 1980s, is a long-lasting trend in indie games. Whereas in the old times this style of visuals was dictated by the physical limitations of the devices, nowadays the same style works just as well to cope with limited production resources. The game developers may not be able to spend much money and effort on visual content.

|

Xeodrifter uses 200×120 pixels scaled

up to fill a 1920×1080 HD display. |

I have only very limited experience in creating computer graphics, but my firm understanding is that 2D graphics is much more straightforward to create in terms of the complexity of the necessary tools. This is, however, not to say that 2D graphics is necessarily easier to create. I believe that regardless of the technical style of graphics, the quality of the end result is always mostly up to the artistic skill of the individuals who put their effort into the creative process.

It seems that retro style "filters" are applied to some games just for the sake of appearing more retro. Sometimes these filters are presented to the player as optional. Switching them on from the game menu can be considered as a fun gimmick for nostalgia's sake or for momentarily shaking up the game for a bit of a different kind of play experience.

Other times the filters are compulsory. Compulsory use of retro filters in modern games can be conflicting. In the old times the "retro style" was an unavoidable fact forced by contemporary technology such as limited graphics chips. Some could only produce 16 fixed colors total in a resolution where pixels were taller than they were wide. Monitors often projected their image on a curved glass surface that made straight lines bend. The picture signal was transmitted through an analog cable that added visible noise. You could even hear a buzzing noise that got the louder the brighter the screen was. These effects were not option but unavoidable limitations that had to be tolerated and worked around. Modern games that use retro filters that bring some of these adverse effects back are essentially putting extra effort in reducing the quality of the experience. I do recognize the appeal of nostalgia from being able to experience the technical limitations of times past. However, forcing that on a game is missing the point. These limitations are not what made some of the old games great. They merely accompanied the old gems. Old classics were great despite their limitations.

One example of applying retro filters with good taste is Galak-Z: The Dimensional. It's a rogue-lite 2D space shooter that is made to look like a 1980s cartoon series. One important artistic detail to carry that feeling is how the pause screen of the game looks like you've pressed pause on your videocassette recorder that's hooked to a cathode ray tube TV. There's warping of straight lines, garble at the top of the screen, color distortion, and even a typical VCR system font.

|

| Galak-Z: The Dimensional looks very retro without getting in the way of gameplay. |

Condensed Visuals

What fascinates me in Downwell is that it manages to pack a lot of meaning into its graphics, especially considering that it goes way past the retro visual style of other games in how narrow its visual bandwidth is (see below). Come to think of it, even early ZX Spectrum games often had more colorful and verbose content than Downwell! Therefore it's perhaps better to call Downwell's visuals minimalistic rather than retro. |

Animation from

Downwell Wiki |

From a technical point of view, the game uses three colors to draw enemies: the background color, the foreground color, and the highlight color. The highlight color is used in two ways. First, when used in small amounts it's both a stylistic highlight and a signal that this is an enemy. All safe objects such as plain walls and breakable props are drawn without the highlight color. The second way that enemies use the highlight color is that when an enemy is not safe to jump on then it's drawn with more highlight color than foreground color. The ample use of highlight color shouts of danger like a poisonous mushroom in a forest. The same logic is used later for traps as well. A wall that will hurt you is drawn mainly in the highlight color.

From a technical point of view, the game uses three colors to draw enemies: the background color, the foreground color, and the highlight color. The highlight color is used in two ways. First, when used in small amounts it's both a stylistic highlight and a signal that this is an enemy. All safe objects such as plain walls and breakable props are drawn without the highlight color. The second way that enemies use the highlight color is that when an enemy is not safe to jump on then it's drawn with more highlight color than foreground color. The ample use of highlight color shouts of danger like a poisonous mushroom in a forest. The same logic is used later for traps as well. A wall that will hurt you is drawn mainly in the highlight color. Another notable thing about the colors is how much the choice of the three colors can express. As you play Downwell you unlock different palettes. It's purely a visual thing and doesn't affect gameplay. The GBOY palette looks unmistakably like the monochromatic screen of Game Boy. The MATCHA palette, on the other hand, looks very much like powdered Japanese green tea. The GRANDMA palette looks to me like a blueberry pie and justifies the name adequately. :-) These mental associations are brought up by the choice of mere three colors.

Another notable thing about the colors is how much the choice of the three colors can express. As you play Downwell you unlock different palettes. It's purely a visual thing and doesn't affect gameplay. The GBOY palette looks unmistakably like the monochromatic screen of Game Boy. The MATCHA palette, on the other hand, looks very much like powdered Japanese green tea. The GRANDMA palette looks to me like a blueberry pie and justifies the name adequately. :-) These mental associations are brought up by the choice of mere three colors.

Some visual cues are not tied to the retro aesthetic but solid game design. As you're falling down the well there is no explicit indicator of which level you're in. That fits well with the minimalistic visuals because the information is there and an explicit indicator would be redundant. You get to choose a new powerup after every level, and the chosen powerups—even transient ones—are displayed at the bottom left corner of the screen. Hence the powerup icons represent your progress through the levels.

Your gunboots operate on charge that replenishes whenever you touch the ground. The maximum amount of charge increases as you collect batteries (or car batteries for a larger increase). The charge is then used up in amounts determined by the kind of gun module you're using. Burst module uses three charges at once and shoots three bullets. Laser module uses five charges and shoots a penetrating beam that only stops at solid ground or a turtle shell. The visual brilliance of the charge meter that you see on the right side of the screen is that you see all the relevant information about charge at a glance. Each unit of charge is shown as a block. The meter is always equally tall so that there's no limit to how far you can stretch your charge reserve. Charge units are joined visually into chunks that display how much charge each shot will use.

|

| Gunboots firing a devastating laser beam. There's still charge for one and half laser blasts. |

Elegance

The minimalistic visual presentation of Downwell seems to match in granularity to the gameplay space. The level of detail that the player has for controlling his character is exactly size of pixels on screen. The colors are just enough to present what is dangerous and what is safe, what blocks movement and what lets you go through. Downwell doesn't have graphical detail in any larger amount than what it needs to convey the state of gameplay to the player. I find this perfect match of visual bandwidth to amount of essential content very pleasing and elegant. I think this is the same kind of elegance that I have seen also in mathematics and programming; being able to concisely express a thing, be it game state, an equation, or an algorithm.

|

Euler's identity (top) links five fundamental mathematical constants in a simple equation.

Quicksort in two lines of Haskell (bottom) expresses the essence of the algorithm as simple, executable code.

|

Downwell is a delight to play. It has packed a lot into a very minimalistic presentation, it's got extremely responsive controls and well thought out gameplay. It's witty and contains delightful little secrets. If you're into retro action and have a chance to check it out, I bet it's worth the time.

Sidenote

Because I'm so inclined, I want to write out definitions for the concepts of visual bandwidth and gameplay space that I used above. Downwell's elegance comes from how they "match in size."Visual bandwidth is the amount of information that can be encoded into the visual stream that a game presents to the player. To rule out silly applications of this term I'd only consider encodings that are legible by a normal human being. So, visual bandwidth is not the bit depth times number of pixels times screen refresh rate. Rather, it's a measure of the style of how a game presents itself considering the guidelines of its chosen visual style. If a game decidedly uses only dark and drab colors then its visual bandwidth is narrow because information cannot be encoded into distinct colors. If a game likes to present information in full sentences of written text then it has a wide visual bandwidth at least when it comes to conveying narrative. It's also possible that a game utilises some clever graphical presentation that can deliver narrative with an even wider visual bandwidth than text-based presentation could. And even though text may have a wide bandwidth for presenting narrative it probably has a very narrow bandwidth for presenting spatial information in a fast-paced shooter.

Gameplay space is the collection of possible game states. A game with many independent objects will have an enormous gameplay space. Only state that essentially affects gameplay should be included in gameplay space. Things that are just for show are not relevant for this concept.

Terrific, as usual. Thanks Ville! :o)

ReplyDeleteI'm also really anxious to understand the secrets behind the retro style. Not only this pixellated or bit-depth-deprived graphical presentation in video games, but also other echoes from the past media, like grain or black & white photographs, or the noise in an LP record. I'm literally astounded by the strength of the effect that they have on people today, given they were merely non-optional technical limitations of their times.

Definitely an interesting angle for future reviews & ponderings. :o)

By the way, Ville, you just might love the Galak-Z soundtrack, by scntfc. Come to think him, I'm about to write a short piece about another game he's also so brilliantly composed for, Oxenfree. Which also boasts rather lovely graphical "glitches". :o)